Museum projects are the top of the project food chain for most project managers. They often require the longest amount of time for planning and the greatest commitment of time, staff and resources for implementation. Most museum relocation or infrastructure projects are two-way projects that require several years to complete. Museum projects tend to require a great commitment over an extended period of time and successfully completing one can define a project managers career.

Museums will vary both in size, scale and in mission statement. A museum can be funded privately, publicly or it can be a government institution, but all museums are cultural caretakers. Whatever action they take with an object the museum has to consider the affect their action will have on its condition and how their actions impact the objects availability for future generations. A collection can be fine art only or it can be fine art and cultural objects, combining art, history and science.

The more diverse a collection, the greater the number of specialists will be required. These will all be people you will need for information and often for authorization. When approaching a project, you are looking at both the physical projects needs and the percentage of difficulty of the project’s environment. Any museum will have multiple levels of authority, they offer limited direct access to decision makers, they have multiple layers of rules and regulations and they require multiple inspection check points. A museum’s bureaucracy needs to be considered as a great potential for delays. Museums require more meetings that other institutions and they require more time to decide. This is because the decision needs to be vetted or approved by more people. The caretakers for a museum’s

collection will be highly trained and specialized creating multiple individuals you will need to communicate with regularly on your project. These include directors, collection managers, conservators and registrars as your main points of contact and then as you need to contact other areas you will meet other managers that you need to communicate. These include building, security, storage and loading dock managers. You will not have free access or free range of motion within a museum. Your movement will be restricted, and you will most

likely be assigned security escorts to monitor you and your staff while you work and move within the building. A museum’s guidelines for materials and handling will be detailed, specific and will often be part of the written agreement. Most museum’s exhibit a fraction of their collection so they are less likely to be concerned with immediate access. Objects may go into long-term or “deep” storage. Materials and packing methods will be chosen for

their safety and longevity. Archival materials and crates will be more prevalent than on a commercial gallery pack. Museums are public venues and your labor and actions may be visible to the public. The contractor’s staff becomes a representative for both their company and the museum. Museum’s will have strict guidelines for protocol outlining how you and your staff should act, appear and communicate while working in the museum. Many museums are union houses which means there will be limits to what work you can do within the building, the hours you can work and strict guidelines on staff interaction and equipment usage. Be aware that the greater the number of people responsible for an object, the more people required to decide, the greater the number of regulations and obstacles and checkpoints all add up to the greater the amount of time the project will require to complete and the greater the potential for delays during the project. All of the preceding, including the potential for delays needs to be considered when budgeting and planning your project timeline.

Museum projects are high profile and vary in scale, but the intent is almost always that part of the collection needs to relocate. This could be an exhibition that needs to travel or an entire collection that needs to be moved to another location. A job well done will be visible throughout the industry as will a job poorly done. Museums will require quotes well in advance for the project for fund raising purposes. Because of their need to bookmark budgets

and plan several years in advance you need to consider cost inflation when proposing

a budget. A museum project will generally have a set budget raised from grants and donations and they will not exceed whatever level has been set. Within their budget there will be budget lines for the different aspects of the project. Funds rarely cross budget lines.

Museum projects will stay closest to the original, idealized plan that you will have drafted before attempting to add the locations specific variables. That does not mean the project won’t be distorted, it will, but it will at least still be recognizable. I’m sure many people that have managed museum projects are thinking “are you kidding me!” but considering the

various areas in the industry that require quoted and controlled events, or projects, a museum project is the least likely to take a left turn and become something else. If a museum contracts you to move collection “A” then no matter what else was added or deleted at the end of the contract, collection “A” will have been moved. Once the project is implemented there will be less attempts to interfere with your plan and to pull or redirect your staff

to the problem du jour.

Museum projects do require a considerable amount of communication, more so than most projects. Not that other areas of the industry do not want information, they just require less than a museum requires. This is not a criticism of museums. The increase of communication required is a direct reflection of the unique variables that you need to consider when quoting a project. The labor structure of a museum compared to the same structure for a commercial gallery or a private collection dictates that more individuals will need to be in the loop because more individuals have the authority to make a final decision. Any decision that is made on a project that impacts the collection will require the inclusion of anyone that could possibly be affected by it. Any decision or action made affecting the project needs to be shared in writing, so that each stake holder has the opportunity to respond.

The primary variable when considering museums for projects is that they are larger and busier than most other institutions. They also have more rules governing the objects and facility, more security in place and more people in positions of authority that need to be included in the discussion and decision-making aspects of the project. Most projects other than museums may have a few, two to four, stakeholders that you need to communicate with. Choose one from each group; the owner/director, CFO/accountant, gallery manager/preparator/collections manager then add a registrar, and these are your typical industry projects stake holders. With museums you can expect a dozen or more. Take one from each group from above then multiply by the number of departments represented in the project, then add conservators, a few facility department heads and possibly an interested board member.

The typical chain of command in the arts outside of a museum is very narrow at the top and very wide at the bottom, less like a pyramid and more like a chandelier. Museums also

have a chain of command, but it tends to resemble a square more than a pyramid, wide at the top, wide in the middle and wide at the bottom with more individuals in place that have a say.

Acting as a communication hub is only one of your expanded responsibilities. Your primary project management responsibility will be to not only manage but to control the budget and to control the contingency delays. Other industry projects budgets usually reflect the needs of one or a few individuals. Museums present multiple hierarchies which means more areas that will have unique needs that they hope will be satisfied by the project. You will receive multiple requests for upgrades or addendums to the project. all requests have validity, but all cannot be satisfied. Projects within a large institution often leave some areas happier than others. These sorts of request often require a review of the budget and several meetings to discuss what can and what cannot be added to the budget. Work stoppages for a variety of reasons can also be greater in museums basically because they have more people that can stop the work. A stoppage under fifteen minutes would normally be absorbed in most projects but because of the potential for a great number of these on a museum project they

need to be considered contingencies to control stoppages you will need to set up paper blocks. Requiring written requests named and dated for each contingency request usually keeps these requests to a minimum.

Besides controlling and documenting the budget you will need to tightly control the timeline and schedule. You will need to have daily goals in place and communicate those goals regularly in order to control panic changes that would throw your schedule off kilter. Your reports will be regular, no less than weekly and depending on the type of project you may need to provide status reports more frequently. Daily email updates are not unusual. Your report would provide general information on the time line and budget and on overall progress and any anticipated problems. Daily updates of this nature would be to all project stake holders. You would then need to present detailed reports and reviews of the project at face to face meetings with the upper tier of stake holders.

Based on all of the above museum projects can be slow and methodical. They are well articulated and documented with activities often planned down to the hour. Little is left to chance. You will need to include the multiple check points that a museum requires into your packing time and schedule. You will need to base your quote on the methods and materials that they are outlined in your contracted agreement. You will need to be clear and accurate in your scheduling and billing. Museum invoices are not final totals. Museums will require itemized listings of all actual expenses billed to the project. Museum’s will be the most likely to have a project plan already in place. You will need to train your staff for the project so they understand the museum’s protocols as well as their methods. Working quickly may not be seen as an asset and again, communicating every move and discussing every decision is essential.

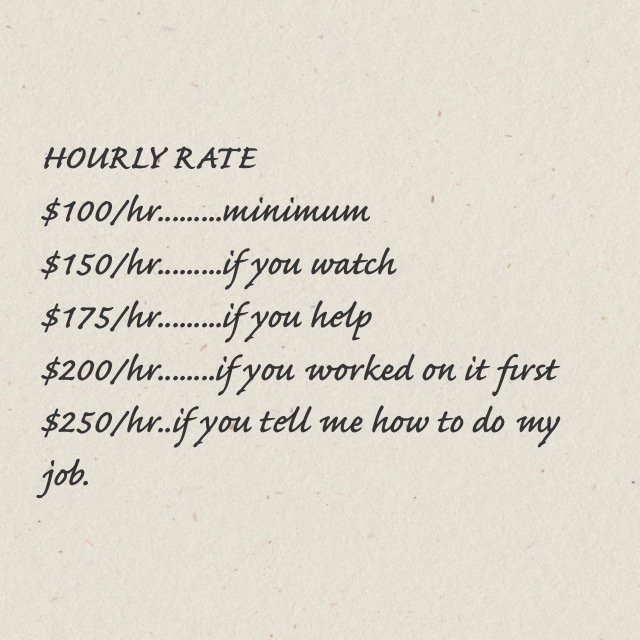

Any institutions communication requirements and the number of individuals in positions of authority over the collection are two of the more important variables to keep in mind as you’re developing your budget and timeline for a museum project. An institutions willingness to accept risk is another factor to consider. The more hands on the art, the more time spent discussing options and the less risk allowed translates into more time required & time is money. There is a joke sign about rates in every plumber and electricians shop, the thing is it’s true.

As you can see from the number of variables, the attention to detail,

accuracy in quoting and scheduling and the highest quality of methods and

materials required museum projects are the standard that all other industry

projects are measured against.

Museum projects are low risk events and museums have the least tolerance for

risk of all the venues.

Next blog: Considering commercial galleries.